Contemporary emerging Europe is a hub of car manufacturing, although with the exception of Škoda in Czechia and Dacia in Romania, the overwhelming majority of vehicles produced in the region are adorned with the badges of foreign brands.

The concept of a national car seems largely to have been forgotten, although Poland’s current attempt to get back into the game with its all-electric Izera model bucks the trend.

In the not so distant past, however, things were very different. Most countries in the region wanted to produce affordable vehicles themselves, giving rise to some iconic models which are today fondly remembered, their unreliability largely forgotten.

We have put together a short list of some of the most iconic cars (and one moped) that remain powerful symbols of a bygone era.

Polski Fiat 126p (aka Maluch)

The introduction of the Maluch (little one) on the Polish market was a momentous occasion. Before 1972, Poland did have an affordable offering for motorists, the Syrena, produced by Fabryka Samochodów Osobowych (FSO) but the car was outdated and only limited quantities were made.

At the same time, limited imports from other Eastern Bloc countries and the virtual impossibility of getting a hold of a Western-produced car (the złoty was not convertible and the free market is not exactly compatible with a top-down planned economy) meant that by 1971 there were only 556,000 passenger cars in the entire country.

So when the Maluch (officially the Polski Fiat 126p) came out, it was a game changer. Despite being compact (to say the least) it was also the de facto family car in Poland. Families heading off on holiday, suitcases tied to the roof rack, were a common sight throughout the 1970s and 1980s.

In total, some 3.3 million units were produced, 2.4 million of which were for the Polish market.

The Maluch was so popular, and production capacity so limited, that families would have to be put on a waiting list for up to two years, or even in some cases longer. When Poland ditched communism in 1989, there were still many people who had not received their Maluch despite pre-paying for it. The government choose to reimburse this money, with no time limit for claims. Even today, it’s estimated that several hundred people may still be eligible to receive around 3,000 euros under the scheme.

Due to its ubiquity, the 126p is a true cultural icon in Poland. However, the honour of having Pope John Paul II ride in a Polish car was reserved for the Maluch’s bigger brother — the Polski Fiat 125p.

The Maluch would have to make do with Adrien Brody, in the 2013 movie The Third Person.

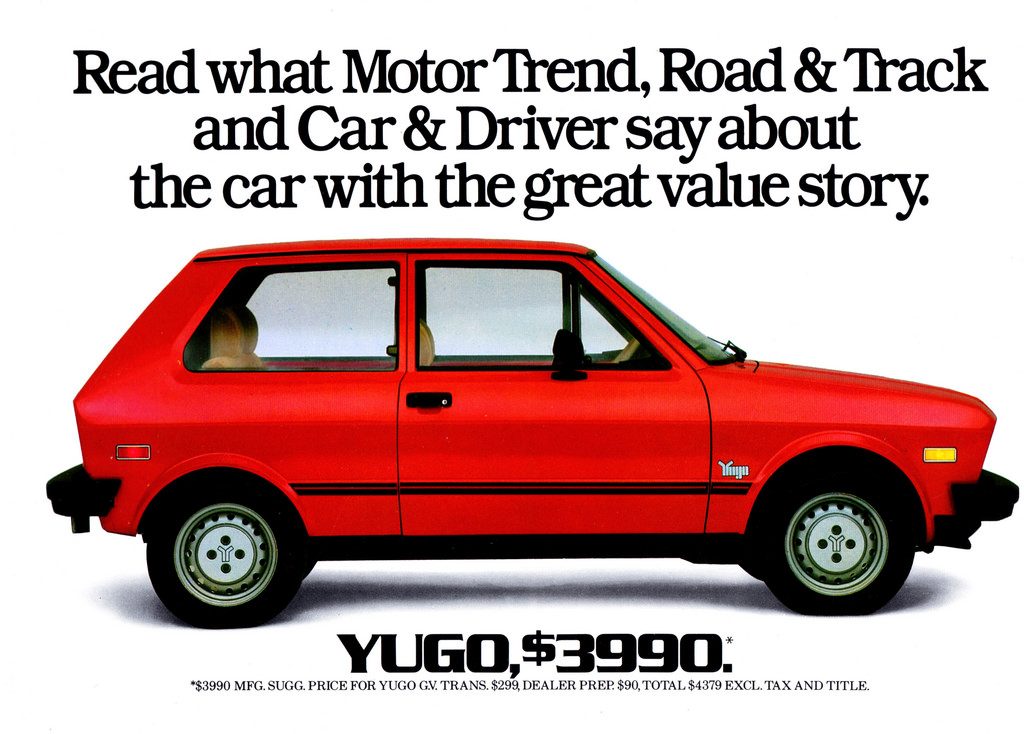

Zastava Yugo

The Yugo is a car that needs no introduction, as its infamy lives on to this day.

Car Talk, the venerable auto programme produced by America’s National Public Radio, declared it the worst car of the millennium in 2011.

“At least it had heated rear windows—so your hands would stay warm while you pushed,” said one listener of Car Talk.

Simply put, the Yugo was cheaply and poorly constructed (although it is said that those made between 1988 and 1991 were of a slightly higher standard).

None of this stopped the manufacturer, Zastava from producing many variations. The Yugo Florida was the luxury sedan version. There was also the Yugo Cabrio, the convertible.

Had the Yugo stayed in Yugoslavia it probably would never have earnt the poor reputation it has today. But a fateful decision to try and sell the car in the United States in 1984 meant that the Yugo would become globally infamous.

Sold for a pittance (it is still the cheapest car ever sold in the US, even adjusted for inflation), it quickly earned the reputation of a lemon. An ambitious campaign that featured front-page articles in The New York Times, The Los Angeles Times and The National Enquirer ended up probably doing more harm than good, once the promises were actually put to the test in real world conditions.

Still, some Yugo owners say that with proper maintenance, the car was not so unreliable, and that the bad image it eventually ended up with was tied more to people treating affordable cars as disposable and not servicing them properly.

Ultimately, it must be said that, in Serbia at least, the car did fulfill its stated purpose. It was cheap, affordable, easy to fix due to its simple engine, and reliable enough to get people from point A to point B. Some would call the ride it offered uncomfortable, others might call it pure, as the Yugo was also very light on safety features.

Dacia 1300

Romanian carmaker Dacia (these days owned by Renault) is currently best known for its Logan model, a small, affordable and impeccably reliable family car.

It is in many ways the successor of the Dacia 1300 (later 1310), based on the Renault 12 and first produced in 1969. It would be a stalwart of Romanian motoring for 35 years. Any photo of a Romanian town or city from the 1970s and 1980s will feature Dacias, and Dacias alone.

In addition to serving as Romania’s affordable family option, the car was also meant to reduce Romania’s reliance on imports and to cultivate economic relations with Western Europe, France in particular.

Just like in Poland, there were waiting lists for the car, years long: just as well, for even though it was termed “affordable”, it still cost three average yearly salaries.

Unlike the Yugo, the 1300 would end up being viewed (mostly) positively. For its time, the car was much more advanced, safer, reliable and – perhaps most importantly – comfortable, than most other cars made in the Eastern Bloc.

Nevertheless, the improved reliability was relative: they would still break down frequently. Older Romanians insist that those made in the first four of five years of production were the best, as they were closer to the original Renault 12 blueprints.

In all, the 1300 and 1310 variations, of which there were many, sold a combined 1.9 million units before it was discontinued in 2004.

Tomos Mopeds & Scooters

No, it’s not a car, but it’s Slovenia’s claim to fame. Serving as many a young man’s introduction to the biking world, the various mopeds produced at a factory in Sežana (Tovarna motorjev Sežana) were – within Yugoslavia – as much an icon as the Yugo.

While Tomos also made motorcycles and scooters, it was the moped line that bred the legend. The first models appeared in the mid-1950s under the name Colibri. In 1959 the company made 17,000, and the Colibri T 12 instantly became the most popular moped in the country.

Indeed, the popularity of Tomos is impossible to understate. In many parts of Yugoslavia, the name Tomos became a genericised term for moped, still used by many to this day.

So successful was Tomos that it ended up opening a factory in The Netherlands, where the mopeds also became very popular.

In the 1970s, the company found additional success with light motorcycles such as the APN-4MS, which had simple one-gear engines, making them easy to ride and maintain. The light and affordable mopeds and bikes became a hit both with young riders and rural populations.

For the former, the Tomos was a fun way to get around, for the latter it was often the only way to get around as many villages lacked paved roads and public transportation. Rural poverty played a part too, as many villagers were unable to afford even the cheap Yugo. Various models, but especially the APN-4MS, were a common sight in Serbian villages well into the 2000s.

Despite a long and brave attempt to stay afloat after the collapse of Yugoslavia, Tomos eventually filed for for bankruptcy in 2019. The whole of the former Yugoslavia mourned.

The Wartburg and the Trabant

No list of iconic Eastern Bloc cars would be complete without East Germany’s Trabant and Wartburg.

In Germany, the two cars have acquired almost mythical status, and thanks to exports, other countries in the east also got to know them (and, belatedly) to love them.

The Trabant follows the familiar theme of being intended as a cheap family car with very modest ambitions. It got you from one place to the other (most of the time), and really didn’t do much else.

In fact, it’s the things that the Trabant didn’t do that it’s most remembered for. First off, the car’s body was not made of metal (the chassis was steel, however) but duroplast, a close relative of formica and bakelite, a fact immortalised in Emir Kusturica’s Black Cat White Cat in an unforgettable scene of a pig chowing down on a Trabant’s body.

Furthermore, the 1980 model did not feature a tachometer, had no indicators, no fuel gauge, and drivers had to pour a mix of oil and gasoline directly under the hood. Even more than the Yugo, the Trabant was poorly put together, completely unreliable, loud and slow.

And yet East German citizens waited up to 10 years to get one of their own, with some even choosing to pay double the official price on the second-hand market.

Despite, or maybe because of, its overall awfulness, the Trabant remains a potent symbol of East Germany. In 2019, the 30th anniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall, hundreds of Germans participated in a parade riding in Trabants and Wartburgs. Among car fans, the Trabant has found a second life with car tuning and rally enthusiasts.

On to the Wartburg, which believe it or not, was considered the luxury option at the time. For one, it was made of metal. For two, it was a lot roomier. And it managed a top speed of 120 km/h, if only while going downhill, as people used to joke.

Of the several Wartburg models, the 1965 353 (aka The Knight) is the one that is most fondly remembered. But the most iconic thing about the car is not its boxy design or its size, it’s the large plume of smoke it left in its wake, thanks to its two-stroke engine.

In 1994, the Serbian rock band Atheist Rap had this to say about the Wartburg:

Wartburg limousine, the longest machine / Four metres of tin, five meters of smoke

Wartburg ceased production soon after the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1991, when the VEB Automobilwerk Eisenach, the factory that made it, was acquired by Opel. Today, there are still plenty of road worthy Wartburgs. Due to environmental regulations however, they are no longer street legal, but have found a new home in rallying.

Unlike many news and information platforms, Emerging Europe is free to read, and always will be. There is no paywall here. We are independent, not affiliated with nor representing any political party or business organisation. We want the very best for emerging Europe, nothing more, nothing less. Your support will help us continue to spread the word about this amazing region.

You can contribute here. Thank you.

[…] Unreliable, uncomfortable legends: The iconic motors of emerging Europe was originally published on Emerging Europe. […]

[…] Read more here: The iconic, legendarily unreliable cars of Eastern Europe […]

[…] Unreliable, uncomfortable legends: The iconic motors of emerging Europe […]