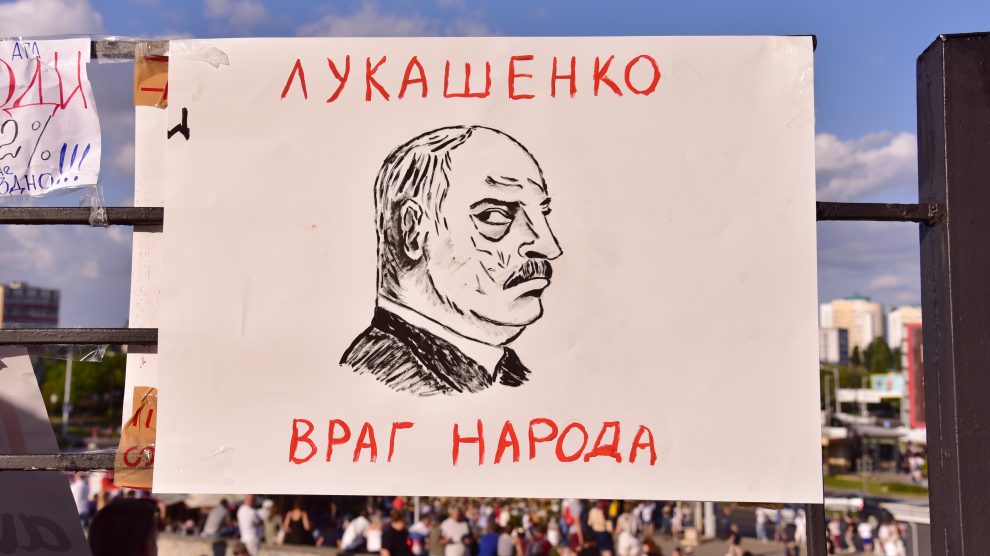

A year on from a fraudulent presidential election, two horrifying incidents have this week served to offer a timely reminder of just how far the regime of Alexander Lukashenko in Belarus will go to stay in power.

Early on the morning of August 3, the body of Vitaly Shishov was found hanged in a park in Kyiv, a day after he had been reported missing having failed to return from a jog.

- Belarus civil society hit by new wave of arrests

- Why Belarus is weaponising irregular migration

- What next for the EU’s Eastern Partnership?

Police in the Ukrainian capital have opened a murder inquiry into the death of Shishov, who led the Belarusian House in Ukraine, an NGO helping people who have sought refuge in the country following the violent crackdown against the opposition in Belarus that followed a fraudulent presidential election last year.

Ukraine, along with Poland and Lithuania, have for the past 12 months been the favoured destinations for Belarusians fleeing persecution at home. According to friends, Shishov left Belarus last October having taken part in demonstrations against the country’s president, Alexander Lukashenko, in the city of Gomel.

Arytom Shraimban, a Belarusian political analyst and founder of the Sense Analytics consultancy, who is also now based in Kyiv, says that Shishov’s death has sent “shockwaves” through the community.

“However,” he tells Emerging Europe, “I would not rush to judgement about whether there was politics behind it. We need more details from the police.”

Shishov’s death came just a day after a Belarusian athlete competing in the Tokyo Olympics was granted a humanitarian visa by Poland after refusing her team’s order to fly home early.

Sprinter Krystina Timanovskaya said on August 2 she had forcibly taken to Tokyo’s airport for criticising coaches over their decision to enter her in the 200 metres – for which she had not trained – and voiced fears for her safety.

Timanovskaya said officials had come to her room and given her an hour to pack her bags before being escorted to the airport. She says she was “put under pressure” by team officials to return home and asked the International Olympic Committee (IOC) for help.

Belarus says she was removed from the team because of her emotional state.

Having been granted a humanitarian visa by Poland, Timanovskaya will fly to to Warsaw on August 4, to be joined by her husband who – fearing for his own safety – fled Belarus for Ukraine.

Heather McGill, Amnesty International’s Eastern Europe and Central Asia researcher, said that sport in Belarus was subject to “direct government control” under Lukashenko.

“Athletes are favoured by the state and honoured by society, and it is not surprising that athletes who speak out find themselves a target for reprisals,” she said.

Belarus back in the spotlight, a year on

The death of Shishov and the apparent attempted forced repatriation of Timanovskaya have again put the spotlight on Belarus, which has been ruled by Lukashenko since 1994.

Last year, nationwide protests over his disputed re-election were violently repressed by the country’s security forces. As many as 35,000 people have been arrested over the past year, and hundreds remain in prison.

According to human rights group Viasna, “at least” 604 political prisoners are still being held in the country’s jails.

The protests were sparked by Lukashenko declaring himself the winner of the election shortly after voting closed on August 9, 2020, officially taking an implausible 80 per cent of the vote.

By any objective measure however, Lukashenko lost the election to Svetlana Tikhanovskaya, who only stood for the presidency after the candidacy of her husband, Sergei Tikhanovsky, a popular YouTuber, was annulled.

Mr Tikhanovsky was later jailed, and is currently on trial for fraud charges that he denies, and which he claims are politically motivated.

Other potential rivals of Lukashenko suffered the same fate as Sergei Tikhanovsky, including Viktor Babaryko, the former head of a major Belarusian bank. Babaryko was arrested in June of last year – also on fraud charges – and denied the opportunity to run against Lukashenko in the August election. In July 2021 he was jailed for 14 years.

Valery Tsepkalo, the founder of the Belarusian High-Tech Park and another potential rival to Lukashenko, was prevented from running on the grounds that he had failed to collect the requisite number of signatures to support his candidacy in the allowed time frame.

That Svetlana Tikhanovskaya made it on to the ballot paper at all was therefore a major surprise: the only other candidates were allies of Lukashenko whose presence was solely to offer a fig leaf of democratic competition.

The notoriously misogynistic Lukashenko never took Tikhanovskaya seriously and so never had her arrested.

She quickly became a focal point for the Belarusian opposition however, attracting large crowds to her election rallies. Shortly after the election she was forced into exile in Lithuania, from where she has led an international campaign for democratic change in Belarus.

“She is the only opposition figure in Belarusian history who, evidently, got more votes than Lukashenko, so she has a valid reason to be at the centre of the movement,” says Shraimban.

Sanctions

Much of Tikhanovskaya’s campaign has centered on the need for tough sanctions against the Lukashenko regime.

Initially, both the European Union and the United States were reluctant to impose anything other than personal sanctions against leading figures in the regime.

They were finally impelled to take stronger action in June, when Belarus hijacked a Ryanair flight from Athens to Vilnius in order to arrest an opposition journalist, Roman Protasevich.

EU foreign ministers subsequently agreed on sanctions that it is hope will hit Belarus’s key export industries, including oil, tobacco and potash, a potassium-rich salt used in fertiliser, which are all major sources of foreign currency for the Lukashenko regime.

EU banks have also banned from offering loans or investment services.

Tikhanovskaya, who recently completed a 15-day tour of the US during which she met President Joe Biden, was this week in the UK to urge Prime Minister Boris Johnson to remove sanctions exemptions, which she says have blunted their impact.

She told reporters outside Downing Street she had not discussed “concrete” actions the UK might take with Johnson, adding that this would require “further work”.

But asked if she thought such help would be offered by the UK, she replied: “I am sure.”

She said she saw in Johnson “a person who really shares common values with Belarusians”.

Tougher sanctions – which, following events in Tokyo could now also include sporting sanctions – appear to be the best chance of bringing about change in Belarus, given that the grassroots protest movement has been quashed so thoroughly.

One Belarusian woman, who asked to remain anonymous, told Emerging Europe that, “this is now a country where even wearing white and red clothes is viewed as an act of rebellion. If people wonder why the protests ended, they should come here and try to protest.”

She was referring to the Belarusian authorities routinely arresting not only those people who fly the opposition white-and-red flag but merely wear clothes in those colours.

While there could be some new demonstrations against Lukashenko this weekend as Belarus marks one year since the stolen election, Ayrtom Shraibman says that the protest movement is effectively dead.

“Lukashenko crushed it last autumn,” he says.

But that does not mean the dictator’s position is secure.

“He is more secure than he was in mid-August last year, but historically, before 2020, his position was stronger than today. He lacks popular support, and can’t run the country without repression.

“He constantly makes unnecessary mistakes (the Ryanair incident, the Timanovskaya case) because he has got himself into a besieged, fortress mentality. This is not a very stable situation to my eye.”

Unlike many news and information platforms, Emerging Europe is free to read, and always will be. There is no paywall here. We are independent, not affiliated with nor representing any political party or business organisation. We want the very best for emerging Europe, nothing more, nothing less. Your support will help us continue to spread the word about this amazing region.

You can contribute here. Thank you.

Add Comment