The apparent poor health of Belarus dictator Alexander Lukashenko, who reappeared in public this week having been taken ill on a recent visit to Moscow, has raised questions about the country’s future.

Alexander Lukashenko, dictator of Belarus, was one of few foreign leaders to stand alongside Russia’s Vladimir Putin in Red Square on May 9 for Moscow’s annual Victory Day parade. Sporting a conspicuous bandage on his right hand, Lukashenko looked far from the best of health as he surveyed the troops passing below his Kremlin vantage point.

Hours later, Lukashenko was conspicuous again: this time by his absence from a lunch Putin had organised for foreign leaders attending the parade. So few were they in number (only the leaders of Armenia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan attended) that they all fitted around a single table, modestly sized by Kremlin standards.

That there had been no time to remove the empty seat reserved for Lukashenko suggests his absence from the lunch was very last minute. Rumours naturally abounded that he was dying – or was already dead.

- Belarus’ civil society fights for a future in Europe

- In its struggle to hold on to power, the Lukashenko regime risks Belarus’ future

- Pressure mounts to ban Russia, Belarus from 2024 Olympic Games

From Minsk, silence, until he reappeared in official news footage a week later, on May 15, wearing an army uniform, heavy makeup and a bandage on his hand – this time the left. No explanations were given for his absence from public life (including Belarus Flag Day on May 14, an event Lukashenko has invariably attended for decades).

In a clear attempt to pre-empt rumours that the footage was pre-recorded, Lukashenko was heard discussing Russian aircraft shot down over Ukraine the previous day. The dictator was unquestionably alive.

But what if he weren’t? Speculation over the current state of his health is purely that – speculation – but during his absence policy makers from Minsk to Moscow, Warsaw to Washington, could have been forgiven for planning for what happens should the 68-year-old Lukashenko suddenly depart the stage.

An international pariah

Lukashenko has ruled Belarus since 1994. A former collective farm manager, his entire presidency has been marked by nostalgia for the Soviet era, and occasionally even for the Soviet Union itself. In 1991, he was the only deputy of the Belarusian parliament to vote against the Soviet Union’s dissolution.

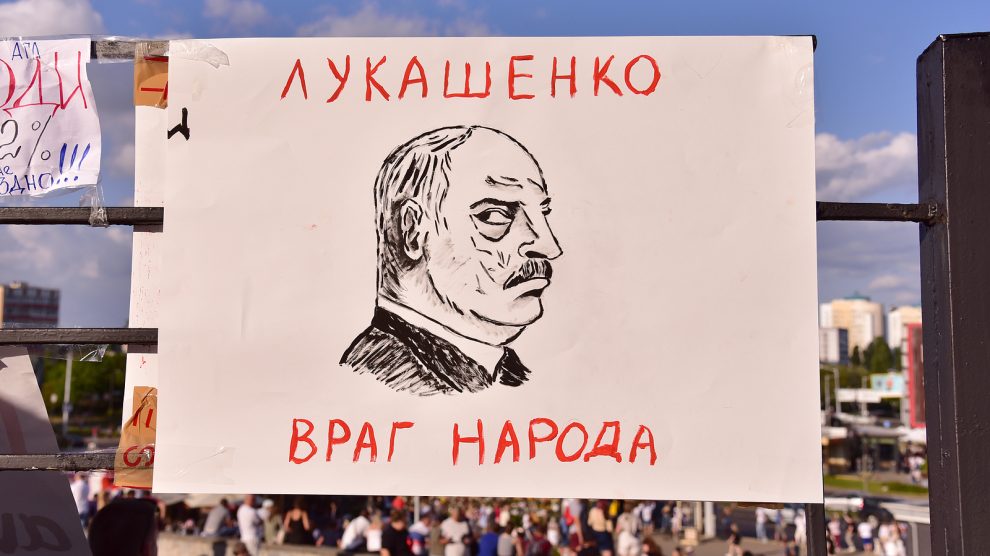

Used to winning uncompetitive elections handsomely (and having changed the Belarusian constitution to allow him to serve several terms in office), on August 9, 2020, Lukashenko declared himself the winner of the country’s latest presidential election with an implausible 80 per cent of the vote.

By any objective measure however, for the first time in nearly three decades Lukashenko had lost the election, to opposition candidate Svetlana Tikhanovskaya.

Widespread protests followed immediately, met with brutal force by the Belarusian security services which remain loyal to Lukashenko. Tikhanovskaya was forced into exile in Lithuania, her husband (who had been barred from standing in the election himself) and campaign team arrested along with tens of thousands of protesters.

Belarus, which had slowly been engaging with the European Union and gently reforming and opening its economy, at once became an international pariah.

Lukashenko’s continued authoritarian rule (which included the state-sponsored hijacking of a Ryanair flight in May 2021 to facilitate the arrest of a dissident Belarusian journalist) and support for Russia’s war on Ukraine have done little to change the country’s status.

While the Belarusian leader has refused to commit forces to the invasion, he has aided Moscow by allowing his country’s territory to be used as a base for launching attacks on Ukraine.

The future

“There are many rumours about the dictator Lukashenko’s health,” Tikhanovskaya, who continues to lead the Belarusian opposition movement from exile, said on May 15.

“For us, it means only one thing: we should be well prepared for every scenario. To turn Belarus on the path to democracy and to prevent Russia from interfering. We need the international community to be proactive and fast.”

Quite what the international community could do is debatable. NATO will not risk war with Russia over Belarus. Russia and Belarus have, in theory at least, formed a Union State since 1999. Although the terms of the Union State treaty are vague, with the only stated aims being the deepening of the relationship between the two countries through integration in economic and defence policy, it would likely be enough for Putin to declare a vested interest in preserving stability in what is his only remaining European ally.

Formally annexing Belarus is doubtful, but in the case of Lukashenko’s death, he would seek to put an ally in office and possibly occupy the country. The latter scenario becomes particularly likely in the case of widespread demonstrations demanding democracy that, in a state of confusion, the Belarus authorities refuse to put down. Putin would almost certainly use the Union State treaty as “legal” grounds for doing so.

The stance of the Belarusian military and security services is likely to be crucial, therefore. With Lukashenko gone, would they arrest pro-democracy protesters to preserve what remains of his regime? Would the army – which has not openly opposed Lukashenko but has consistently refused to join Russia’s invasion of Ukraine – accept a Russian occupation of the country? Given that while Russia probably has the numbers to peacefully occupy Belarus, it is highly unlikely it has the combat troops needed to occupy the country by force.

Vacancy

Alexander Dabravolski, an advisor to Tikhanovskaya, said this week that if Lukashenko were to suddenly pass away or become incapacitated, the opposition would invoke one of six action plans, dubbed ‘Vacancy’.

“We need to make contact with those who are ready to fight in Belarus, we need to make contact with those who are trying to bring about change, with politicians,” he says.

“Basically, we have a ‘plan for victory’, but we don’t know how it would work. Clearly, we need to think about new elections, how to ensure a more or less stable economy and protect ourselves from any revanchism.”

For operation vacancy to be successful, the Belarusian opposition will need support from its allies, notably Poland – which shares a border with Belarus.

Poland, which has accepted and integrated millions of displaced people from Ukraine, would be unlikely to cope as well with another, new wave of refugees from Belarus, should chaos ensue following Lukashenko’s death or incapacitation.

Writing in the Polish edition of Newsweek, analyst Jacek Pawlicki this week called on the country’s president, Andrzej Duda, to make sure that the country has a unified plan for any eventuality in Belarus.

“It is worth involving the opposition in all this now – a democratic and stable Belarus is in the interest of all political forces in [Poland],” he wrote.

The EU should also be making contingency plans. A democratic and stable Belarus is in the interest of the EU, too.

It should at the very least ensure that lines of communication with the Belarusian armed forces, senior diplomats and officials are in place, along with public statements of support for the territorial integrity of the country.

Then should come incentives for a peaceful, democratic transition of power. Political prisoners should be released in exchange for the lifting of some sanctions, with assurances that others would be lifted once a free and fair election to choose Lukashenko’s successor had been held.

The international community’s stick has not deterred Lukashenko from pursuing a pro-Russia, highly authoritarian and anti-democratic agenda. In the case of those who would follow him, carrot is likely to work best.

Unlike many news and information platforms, Emerging Europe is free to read, and always will be. There is no paywall here. We are independent, not affiliated with nor representing any political party or business organisation. We want the very best for emerging Europe, nothing more, nothing less. Your support will help us continue to spread the word about this amazing region.

You can contribute here. Thank you.