Several countries in Central and Eastern Europe – notably Poland – have belatedly realised that hydrogen offers a potentially huge opportunity to divest from coal. But for the region to take leadership in the field, in needs to move fast.

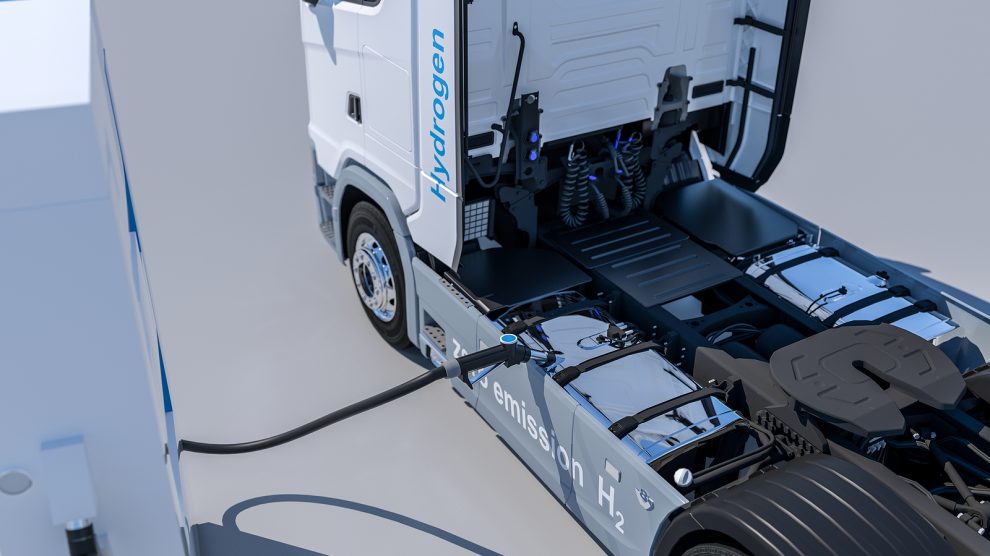

Hydrogen is being hailed by increasing numbers of stakeholders in emerging Europe as a fuel that could play a big role in the decarbonisation of heavy industry and transportation.

Renewable, clean and so-called “green” hydrogen could soon become a replacement for fossil fuel in these sectors, not least in those parts of Central and Eastern Europe that remain heavily reliant on coal.

The European Commission certainly thinks so. According to its own estimates, clean hydrogen could meet 24 per cent of the world’s energy demand by 2050, with annual sales in the range of 630 billion euros. Additionally, this could translate into one million jobs along the value chain.

- Polish Greens demand better, not bigger state to tackle climate change

- Estonia has the cleanest air in emerging Europe, and the rest of the region needs to catch up

- Hungary brings forward coal exit to 2025

To that end, the European Commission unveiled a strategy last year that charts the path to 100 per cent renewable hydrogen which will support the installation of at least six gigawatts of renewable hydrogen electrolysers by 2024, and and least 40 gigawatts by 2030. In this way, by 2050 – once technologies reach maturity – hydrogen could be deployed on a wide scale across sectors including chemicals and steelmaking, two industries that are notoriously hard to decarbonise.

“The development of the EU hydrogen market can play a significant role in achieving the goals of the EU Green Deal,” says Bartek Czyczerski, general director of Business and Science Poland.

“Most notably, hydrogen’s capabilities to ‘store’ energy produced from renewable sources or serve as an alternative fuel – both highly relevant in achieving a zero-emission economy by 2050 – triggered the Commission to draft the European Hydrogen Strategy.”

CEE’s potential

For many analysts, CEE as a region has great potential to take advantage of hydrogen production and transport. Poland is already one of the leaders in hydrogen production, the third in Europe. But as in most of the world — only 0.1 per cent of global production is a zero carbon process — most of it comes from grey or blue sources.

Grey hydrogen is the term for hydrogen extracted from natural gas using steam-methane reforming. Blue hydrogen is that same hydrogen with the CO2 emissions captured or repurposed.

The path to green – which is hydrogen produced from electrolysis of water using renewable electricity such as hydropower, wind, or solar – will be long and costly.

Nevertheless, in February, Poland unveiled an ambitious draft hydrogen strategy that hopes to see the country develop two gigawatts of renewable hydrogen capacity by 2030.

“The plan is very ambitious but can be reached if the support of the Polish government is really significant,” says François Le Scornet, president of Carbonexit Consulting.

“In 2020, many of the hydrogen projects in Poland were launched by state-controlled blue chip companies, which demonstrate the critical existing role of the government.”

Among these projects are Pure H2 and Green H2, both devised by Lotos Group, an oil refiner and retailer. Pure H2 will see the construction of a hydrogen purification installation at its Gdańsk refinery, a sale and distribution station near the Lotos Group plant, and two vehicle refuelling points in Gdańsk and Warsaw.

Green H2 will see the construction of a large scale electrolyser allowing the production of green hydrogen and its subsequent storage.

Another refiner, PKN Orlen, is developing a hydrogen hub in Włocławek that should be able to produce 600 kilogrammes of highly purified hydrogen of transport fuel quality for use in public and freight transport.

PGNiG meanwhile, Poland’s largest gas company, signed an agreement with Toyota Motor Poland in May 2020 to build a pilot hydrogen refuelling station in Warsaw.

Late to the party

Among industry experts, there is wide consensus that Poland can make good on the promises of its draft strategy.

“The potential of hydrogen to enhance the economy is recognised in Poland. There is a huge interest in this technology; Polish authorities are convinced that Poland could be one of the leading countries in this area and could be a transit country for the mixture of natural gas and hydrogen in the future,” says Mona Dajani, energy group leader at Pillsbury Winthrop Shaw Pittman.

Gniewomir Flis, senior hydrogen advisor at the Germany-based Agora Energiewende think tank, believes that Poland has the capacity to meet and even exceed the two gigawatt target, but warns about the tight deadline and the fact that Poland might be “late to the party”.

“The Polish government is looking to develop a homegrown electrolysis champion. The idea is to have a prototype by 2025, and to scale it in the second half of the decade,” he explains. “This is a tight timeline, and further Polish ambitions are late to the party: most of Europe’s electrolyser manufacturers have well-developed products with years, sometimes decades of experience. They won’t be waiting, in fact they are already in the process of building giga factories. The risk is that by the time Poland develops a good electrolysis platform, it will be outmanufactured.”

According to Mr Flis, the biggest risk for Poland is eventually being outdone by renewable hydrogen imports from abroad.

“Whether it’s hydrogen piped from Iberia through Germany, from Ukraine or from Turkey, there are several options, but the trend is clear – renewable hydrogen is likely to become cheaper than alternatives during the 2030s,” he says.

“There are two strategies to hedge against this risk: a more aggressive roll-out of renewables and electrolysers in Poland, or becoming part of international consortia, with the goal of influencing hydrogen network discussions in CEE. Poland has enough heft to take on a leading role.”

One more issue that could affect Poland is what “colour” (i.e. origin) of hydrogen ends up being supported by the EU and its hydrogen-related policies.

Recently, the Polish climate minister, Michał Kurtyka, said that the EU’s hydrogen policies need to be “colour-blind” and that hydrogen technologies should be judged by the level of their emissions rather than origin.

Environmentalists on the other hand have come out against “low-carbon” hydrogen.

“Hydrogen must not become a blanket approval to safeguard the future of the gas industry. Low carbon hydrogen typically refers to fossil-based hydrogen produced from steam methane reformation and coupled to CCS (carbon capture and storage). This has to be avoided as it will deepen the gas lock in effect and create stranded assets,” says Esther Bollendorff, gas policy coordinator at Climate Action Network Europe.

Still, others, like Mr Flis, believe that blue hydrogen could be used to “kickstart” decarbonisation.

“In this context, I would like to draw attention to recent debates on an amendment to EU taxonomy on what constitutes ‘sustainable’ hydrogen. Currently, the proposal is for a 73 per cent emission reduction on a lifecycle basis with respect to unabated fossil comparator. I feel it’s a good compromise, allowing for best-in-class blue hydrogen projects, as well as some grid connected electrolysis during periods of high renewable penetration,” he explains.

The beginning of a revolution

Right now, Poland is not the only country in the CEE region that is looking to take advantage of hydrogen production capacities. Ukraine also wants to be a leader in the hydrogen space in Europe. The country has already tested hydrogen blending in the gas grid, something that others will have to do as well, and is eyeing a capacity of up to 10 gigawatts of electrolysis-produced green hydrogen in its hydrogen strategy.

“To make that happen, they would have to rely on a pipeline going through Poland, but mostly Slovakia and particularly, Czechia. Perhaps it’s no coincidence that the Czechs are included in the original backbone plan. They could also be a link for importing hydrogen from the south. In other words, plenty of opportunities in CEE hydrogen. Leadership on positions is key to unlocking the rewards,” says Mr Flis.

Elsewhere in CEE, Bulgaria and Croatia are also looking to develop national strategies regarding hydrogen, while in Slovakia there is now a Centre for Hydrogen Technologies.

“Hydrogen is not just a new energy carrier, but the beginning of a revolution in the energy system, where Europe is the leader. The EU and CEE has a perfect alignment of conditions for a new hydrogen market and with the Green Deal, a clear sense of direction,” says Ms Dajani.

Unlike many news and information platforms, Emerging Europe is free to read, and always will be. There is no paywall here. We are independent, not affiliated with nor representing any political party or business organisation. We want the very best for emerging Europe, nothing more, nothing less. Your support will help us continue to spread the word about this amazing region.

You can contribute here. Thank you.