The films of the Yugoslav Black Wave transcend borders and time.

Restrained by the cliched post-communist lens, the Yugoslav Black Wave is a film movement often cast aside and overlooked. Its work is too frequently dismissed as only relevant to the Yugoslav era, the poeticised dissident artist struggling under communism, poverty and state repression.

However, to view such artwork through this lens is damaging not only to the artwork itself but also to the viewer, preventing ourselves from extracting our own reality. Zooming in on the work of pioneering filmmaker Želimir Žilnik, it becomes clear that the Yugoslav Black Wave movement is still strikingly relevant, transcending borders and time.

- Is Interslavic the Slavic world’s new lingua franca?

- Five movies from Kazakhstan and Central Asia

- The Colour of Pomegranates: One of the most unique films ever made

After Yugoslav leader Josip Broz Tito’s break from Joseph Stalin and the Soviet Union in 1948, a notable disintegration of cultural rigidity took place, replaced by an avant-garde non-alignment policy. This allowed an expansion of artistic realms, making the Yugoslav art scene one of the most experimentational and unconventional in the region. It was this environment which fostered the birth of the Yugoslav Black Wave in the late 1960s.

Typically characterised by social criticism and dark humour, it is politically subversive and sexual – redefining the standards of cinematic realism. It broke boundaries yet remained broadly unnoticed by the wider world. Notable directors include Mika Antić, Žika Pavlović, Krso Papić and Želimir Žilnik. Some, of course, had success that crossed the Iron Curtain, notably Dušan Makavejev’s WR: Mysteries of the Organism which won acclaim from critics at Cannes. Other works were frequently nominated for Academy Awards and received wide praise overseas.

However, the freedom given to Black Wave artists was not unlimited. WR: Mysteries of the Organism was banned in Yugoslavia and sent Makavejev into exile. Many others suffered the same fate due to the overt anti-communist tones of their work or for depictions of a pessimistic view of society and its development. Validating individualism rather than collectivism was also cause for official displeasure.

A social realism we wish to ignore

Today, it is these same things which makes the work so poignant. The Black Wave deals with a social realism we wish to ignore, the socioeconomic issues of everyday life. It deals with those whose lives are cast aside to the periphery of society, not only applicable to Yugoslav society at the time but any society at any time.

Želimir Žilnik is perhaps one of the movement’s most notable and culturally relevant figures and a closer look at his short films will allow a glimpse into a wider narrative, warning of the dangers of ignoring works such as his.

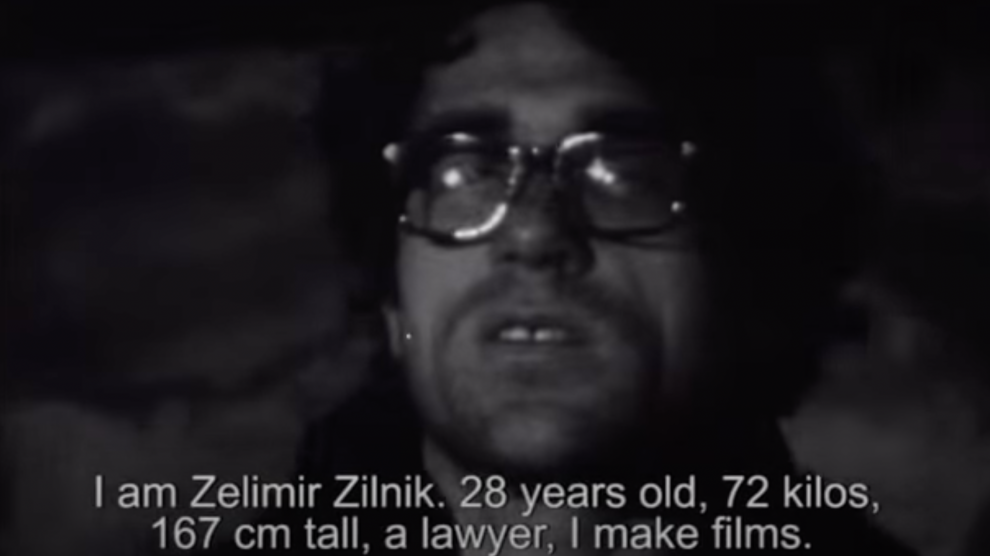

Žilnik’s 1971 Black Film is a 15-minute exploration into the state of homelessness. It opens with Žilnik saying: “These six people are homeless, in this film we try to find them accommodation” and proceeds to introduce the six men, all hopeless and disillusioned with the lack of state support. This is contrasted with Žilnik introducing himself as well off, in a large apartment the state gifted him. He then lets the six men into his flat, and asks the public what he should do with them.

Officials and citizens all respond with a similar answer: I don’t know or suggest vacant spaces such as the fish market or abandoned buildings for them to sleep in. The film ends with no fix, as “It is all the same”. The film roll then abruptly runs out as he is showing the men out of his flat, as if a call to wake up.

Struggle for identity

While it would be easy to cast the film aside as a criticism of the shortcomings of the communist system this would be too simplistic. It needs to be viewed as something broader, about a struggle for a society’s identity. As art historian Boris Buden puts it: “It is about society struggling with art for the true picture of itself, a society in the final struggle for its cultural survival”.

The film was made to go beyond Yugoslav society at the time and to a broader critique of liberalism, society and even art itself. At the beginning of the film Žilnik states “I made a similar film two years ago but it didn’t change anything”. Here, he is calling society’s bluff. The liberal ideal of the benevolent civil society helping the less fortunate find solutions, the artist bringing attention to pitfalls and making the periphery becoming culturally relevant. This is all an illusion according to Žilnik. He is mocking the utopian light that does not reach the periphery of society, leaving those in blackness.

Similarly, his 1968 work Little Pioneers focuses on a group of young teenagers causing disruption, disillusioned with their place in society and often driven to stealing – another segment of society cast to the black. It shows the mistreatment towards them by police, authoritative figures and society in general. It ends with a mothers rage: “These are not normal kids, they are like cattle and should be taken to the reformatory”.

Tangible impact

These themes are undoubtedly relevant to any culture, there is always an outer and a feeling of powerlessness located within. Žilnik is disillusioned with the idea that art and benevolence can actually have a tangible impact. If he walked the streets of London or New York today asking that same question, What do I do with these homeless men? many would have the same answer – I don’t know.

The socially relevant commentaries of the Yugoslav Black Wave are often lost and cast aside. The films are victim to a post-communist lens that casts as a triumph of western liberalism against the failures of communism.

Unfortunately, this was the case not only for Yugoslav art but any art east of the Iron Curtain. Orientalist cliches and pre-existing stereotypes have prevented us from reaping the real benefit of the work. It is not necessarily a critique on the communist regime, but of society itself to which its characteristics are universal. Polish art historian Piotr Piotrowski warns against this perception of an “Eastern European” art history, but rather for it to be viewed as global.

For if there is anything that the Yugoslav Black Wave can teach us, it is cautioning us against the dismissal of artworks based on their context, for more often than not good art can penetrate through context to that of the universal.

Unlike many news and information platforms, Emerging Europe is free to read, and always will be. There is no paywall here. We are independent, not affiliated with nor representing any political party or business organisation. We want the very best for emerging Europe, nothing more, nothing less. Your support will help us continue to spread the word about this amazing region.

You can contribute here. Thank you.

Add Comment