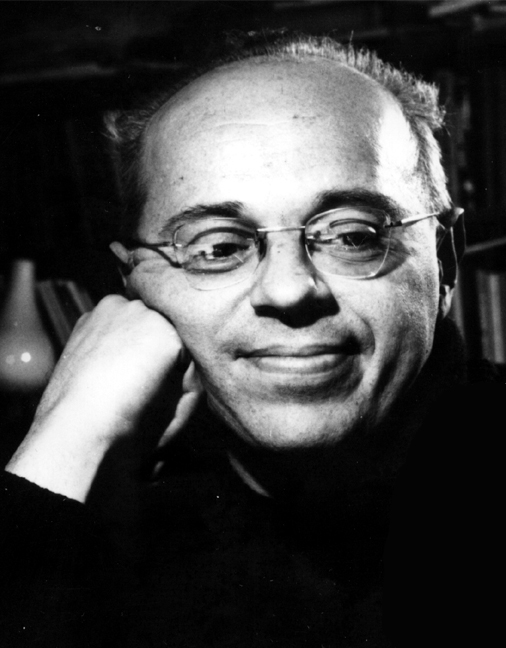

Best known as the author of Solaris, Stanisław Lem has been largely forgotten outside of his native Poland. The Year of Lem – which celebrates the centenary of his birth – aims to change that.

This year marks one hundred years since the birth of Stanisław Lem, whose pioneering science fiction and philosophy of technology oeuvre still captures the imaginations of readers today.

In a world replete with technology, much of which Lem himself correctly predicted decades ago, his ideas remain instructive and relevant.

- Six of the best: Nobel Prize-winning literature from emerging Europe

- Polish comic book heroes set for Netflix adaptation

- Required contemporary reading from emerging Europe

“I think that while Lem’s work is known globally, he is a kind of a forgotten, underestimated classic – he deserves more recognition than he has got so far. He should be read and adapted to screen more often, so that new generations of readers and viewers could get to know him better,” says Jerzy Rzymowski, editor-in-chief of the long-running Polish magazine Fantastyka.

We may well see resurgence of interest in Lem this year, as in honour of the centenary of the his birth, the Polish parliament has declared 2021, “the Year of Lem”.

Survivor

Born into a Jewish family in 1921, in what is now Lviv, Ukraine (then Lwów in the Second Polish Republic), Lem survived World War II as his family managing to avoid being sent to the Lwów Ghetto with the help of forged papers.

Lem worked as a mechanic and welder during war, employed at a German company, and had access to storehouses from which he would occasionally steal and pass munitions to the Polish Resistance. In 1945 Lem, together with his family, was resettled in Kraków, like many other Polish citizens when Lwów became part of Soviet Ukraine.

He started writing shortly after the war, but like all Polish artists at the time he had to contend with strict censorship. It was this censorship that at least partly explains why Lem decided to focus on science fiction, which was a less politicised genre at the time. Even so, Lem himself would later admit that some of his early pieces were compromised by ideological pressure.

Lem’s most productive spell began after the so-called “Polish October” of 1956, which led to citizens and artists alike enjoying a lot more freedom than before.

This prolific period would cement Lem as the greatest science fiction author the country has ever produced.

“For many years Lem’s works were defining the shape of Polish speculative fiction, just as the work of the Strugacki brothers were defining Russian sci-fi. He was a giant and other writers stood more or less in his shadow: being compared to him, relating to him, following his footsteps or trying to oppose his views,” says Mr Rzymowski.

Solaris

In 1961 Lem published Solaris, arguably his best-known work, especially outside of Poland. Solaris was adapted to the big screen twice. Once, memorably, by the Soviet director Andrei Tarkovsky, and much later, less memorably, by Steven Soderbergh.

Lem, who died in 2006 was not a fan of either adaption.

Unlike most science fiction of the era, which imagined aliens as being similar to human beings, Solaris explored how communication could work, or not work, with an entity that is radically different from human beings. This commitment to “hard sci-fi” marked much of Lem’s work and served as a segue into more philosophical considerations of technology.

While there is often a certain dryness to such themes, Lem managed to insert irony and even humour into all his works, something that set him apart from his other “hard sci-fi” peers like Isaac Asimov and Arthur C. Clarke.

This is best seen in his Summa Technologiae, a collection of essays on the ethical and moral considerations surrounding technology and the future.

In this collection, Lem focuses on what society might look like as limitations, both technological and material, are taken away.

The tome is also known as a prime example of Lem’s love for neologisms (something that gave his translators abroad a hard time). Summa Technologiae gave us phantomatics and ariadnology, known today as virtual reality and search engines.

More relevant than ever

This near-prophetic level of predictions makes Lem’s ideas possibly more relevant than ever.

“Behind his ideas about technology there were deeper philosophical thoughts about mankind and civilisation, about human nature. These are very important as we face the biggest challenges in our history and the answers to these questions can decide if we survive or destroy ourselves,” Mr Rzymowski tells Emerging Europe.

As virtual reality becomes mainstream, maybe it is time to start wondering if humans might prefer virtual omnipotence to the limited powers available in real life. And with technologies such as gene editing and nano medicine in the pipeline, the question as to whether technology can potentially outdo evolution is already being asked.

In Lem’s native Poland, he has inspired others to think about these issues too.

“Man in the 21st century is surrounded by technology but does not always know how to use it for his own good. This is our role. We focus on education and on children’s online safety, online privacy, e-administration, the use of innovation in local government institutions and we counteract the digital exclusion of seniors,” says Maciej Kawecki, the president of the Lem Institute, a digital think tank and advocacy group and one of the organisers of the Year of Lem.

Indeed, technology today is often not used for good. The growth of noxious social media use continues unabated, making people depressed and endangering democracy. Surveillance by public and private entities alike threatens to end privacy as we know it. And the less said about online dating, the better.

A visionary conservative

Perhaps there is something to be said for a degree of conservatism when it comes to technology. Mr Kawecki agrees.

“Stanisław Lem liked to call himself a visionary-conservative, emphasising at the same time that he is alien to all extremes – both technocracy, both fiction and non-fiction. For me personally, it’s a great lesson and example in how to be a visionary and yet still understand that we need to be aware that technology can be dangerous and sometimes needs to be supervised,” he explains.

In his 1964 novel The Invincible, Lem coins another neologism — necroevolution, a term he suggested for the evolution of non-living matter. It was one of the first works that put forward the idea of sentient microbots and smart nano dust. While we are still far away from such things, the philosophical implication is interesting. Can human values co-exist with the rational efficiency of sentient machines?

Perhaps fittingly, the novel is now being adapted into a video game by an independent Polish game studio, Starward Industries.

“I feel that we are really on the cusp of some technological breakthrough, and tech is going to steamroll ahead. How will it behave? How will it evolve? Will it evolve by itself!? And if it does, does that mean it becomes life in the way that we know it as now? Those are some pretty out there and forward-thinking questions. The thing is, they were asked over fifty years ago. That’s how far ahead Lem’s mind was,” says Marek Markuszewski, CEO of Starward.

If Lem has indeed been forgotten on the world stage, perhaps his fiction and his ideas will find a new life in the interactive space, a space that Poland is fast becoming am major player in.

Meanwhile, the Year of Lem continues in Poland, where he remains a legend.

“He’s one of those authors that we are super proud of,” concludes Mr Markuszewski.

Unlike many news and information platforms, Emerging Europe is free to read, and always will be. There is no paywall here. We are independent, not affiliated with nor representing any political party or business organisation. We want the very best for emerging Europe, nothing more, nothing less. Your support will help us continue to spread the word about this amazing region.

You can contribute here. Thank you.

[…] Why the work of Stanisław Lem is more relevant than ever was originally published on Emerging Europe. […]

[…] Why Work of Stanislaw Lem is More Relevant than Ever. https://emerging-europe.com/after-hours/why-the-work-of-stanislaw-lem-is-more-relevant-than-ever/ […]

[…] Why the work of Stanisław Lem is more relevant than ever […]

[…] https://emerging-europe.com/after-hours/why-the-work-of-stanislaw-lem-is-more-relevant-than-ever/ 9 […]

[…] Why the work of Stanisław Lem is more relevant than ever […]