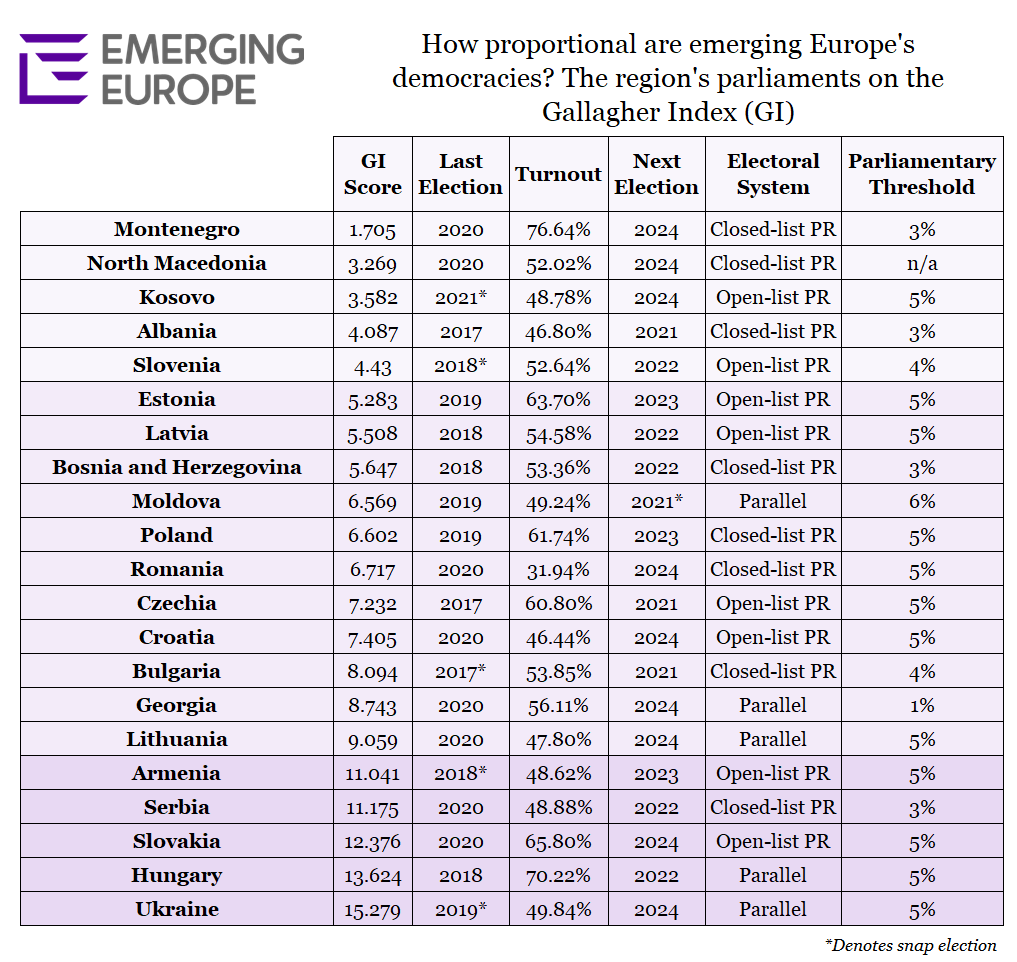

Montenegro’s parliament is currently the most representative of all those in Central and Eastern Europe, according to Emerging Europe’s analysis of the region’s scores on the so-called Gallagher Index.

In democratic societies, elections represent the most direct manifestation of democracy, where the general public chooses who they want to rule over them for the next few years.

Although in the minds of the electorate all votes are equal, and the outcome of the election will be perfectly proportional to the will of the people, the mathematical constraints imposed by the reality of most electoral systems dictates that, in many cases, election results can be skewed.

- Svetlana Tikhanovskaya is Emerging Europe’s Public Figure of Year

- What to expect from Armenia’s snap election

- Britain’s misreading of Poland says more about the UK than it does Poland

A well-known example is the United States’ electoral college system used to choose the country’s president, which wows keen onlookers at how needlessly elaborate and archaic it is. Not to mention how, on occasion, the presidential candidate who wins the most votes ends up losing (as happened in 2016).

Other examples include Canada, where upon winning in 2015, prime minister-to-be Justin Trudeau proudly proclaimed that year’s election was to be the country’s last under a first-past-the-post (FPTP) system.

Four years later, his Liberal party secured a second term in office despite coming second in an election that still used FPTP.

But how can we measure the disproportionality – and unfairness – of an election? And how do the countries of emerging Europe shape up?

The Gallagher Index

One method of measuring the disproportionality of an electoral system is what has become known as the Gallagher Index, created by political scientist Michael Gallagher at Trinity College, Dublin.

Gallgher initially referred to his method as the least squares index: over the years, Gallagher Index has gained more popularity, perhaps in part due it sounding not unlike an Oasis tribute act.

Nevertheless, its initial name offers a clue as to how it measures disproportionality.

The two most important numbers are the percentages of the vote each party receives, and the percentage of seats they end up taking in parliament.

We then subtract the vote share from the share of seats, square the difference, then collate the values for all parties that stood in the election. We then halve the sum, and find the square root, obtaining the Gallagher Index (GI) for that election.

The GI is then reflected as a number that ranges from 0 (perfect proportionality) to 100 (complete disproportionality); the lower the number, the more proportional the outcome of the election.

In practice, any score higher than 10 is considered poor and suggests an electoral system that fails to offer genuine representation of the votes cast.

The countries of emerging Europe (we have excluded Azerbaijan and Belarus from our research, as they are not democracies) all use proportional representation (PR) in one form or another.

The universal adoption of this system at the beginning of their path towards democracy is a prime indicator that it is the fairest electoral system.

Emerging Europe’s worst performers: Ukraine and Hungary

The most unrepresentative recent elections in the region were those held in Hungary in 2018 and Ukraine in 2019. Both countries use a parallel system where the electorate has two votes – one for a local representative, chosen using FPTP, and one for nationwide representation, using PR.

The divided opposition in both Hungary and Ukraine, plus the overwhelming popularity of the ruling party (Fidesz and Servant of the People, respectively) results in nearly all the FPTP seats being taken by the largest party, and the overall result being skewed in their favour.

Parallel systems are in general more disproportionate than those that solely use PR. In emerging Europe, elections which used parallel systems scored an average of 10.655 on the Gallagher Index, whereas those that only used PR scored a much lower average of 6.51.

An ‘outlier’ of the parallel systems is Moldova, whose most recent election took place in 2019 and which scored relatively low. This is in part due to it being the first and last election held under this system, giving little time for voting habits to adapt. The switch to a parallel system from pure PR was done without the consultation of the public and did not prove popular; as a result, from the next parliamentary election onwards (and a snap election may be held this year), it is expected that ‘pure’ PR will once again be applied.

At the other end of the spectrum, the lowest-ranking ‘pure PR’ systems are in Slovakia and Serbia. Slovakia’s high result is down to many parties not reaching the five per cent threshold to enter parliament – its multi-party system means the party that came first, Ordinary People and Independent Personalities (OL’aNO), received barely a quarter of the vote, but a third of the seats in the National Council, to make up for the 21 per cent of votes that went to parties that did not pass the threshold.

Serbia’s election, on the other hand, was held under dubious circumstances and faced a boycott from voters and opposition parties – 3.67 per cent of all votes were spoilt.

Montenegro

Of note is Montenegro, whose most recent election (held last year) scored a mightily impressive Gallagher Index of 1.705, as well as seeing the highest turnout for any election in emerging Europe in recent years, despite being held in the midst of the Covid-19 pandemic – 76.64 per cent.

The 2020 Montenegro parliamentary election was also notable as it marked the first peaceful transfer of power since the legalisation of opposition parties in 1990. Despite coming second, For the Future of Montenegro was able to form a coalition with several smaller parties, toppling the governing Democratic party of Socialists.

Another observation worth making is how, ultimately, voters having a choice over which candidates of a party enter parliament (closed-list vs open-list) does not hugely affect proportionality.

Elections held under closed-list PR scored an average of 5.912, and those under open-list PR scored an average of 7.107 – a difference of only 1.195. The advantage of open-lists, however, is that they arguably provide better local representation, minimising the one downside of a nationwide PR system.

It is important we also discuss the upper chambers of parliaments, not represented in our table, as only four countries in emerging Europe possess them.

An interesting example is Poland, which uses FPTP for elections to its Senate, yet scores a not-too-bad 6.726. This is because, with elections to the Sejm being purely PR, voters can afford to vote for smaller parties who better represent their beliefs, while the Senate becomes a secondary vote for those parties that stand a chance of forming a government.

This is illustrated by looking at the vote share for the two largest parties: in the Sejm, Law and Order (PiS) and Civic Coalition received a combined 71 per cent of the vote, whereas in the Senate they received a much higher 80.22 per cent.

Romania’s Senate, on the other hand, is noteworthy for not being noteworthy. It is one of very few upper chambers in the world which is not only elected in the same fashion as the lower house (closed-list PR), but which has virtually no distinct attributes relative to its lower counterpart. With the same party makeup and responsibilities, it defeats the purpose of having a second chamber entirely.

Finally, (disregarding Bosnia and Herzegovina’s upper chamber, whose members are appointed as opposed to being directly elected) the most disproportionate result is that of the Czech Senate, which scored a staggering 23.477 on the Gallagher Index in 2020.

This is because elections to the Czech Senate are staggered, a third of seats being diputed, every two years, using a two-round system (such as that used in France). Because the ‘run-off’ second round of the election almost always results in a victory for one of the larger parties, small parties typically don’t stand a chance despite receiving more votes in the first round than they would under FPTP.

‘None of the above’

Bulgaria’s upcoming parliamentary election (to be held on April 4) could prove pivotal, with the opposition looking to remove the ruling GERB party from power. Bulgaria is unique in emerging Europe for having a “none of the above” option, which received a solid 2.5 per cent of the vote in 2017, causing a slight increase in the country’s Gallagher Index score.

Something it has in common with its neighbours in the region, however, is the PR electoral system.

Despite the struggles the region faces, the topic of electoral systems is one that most countries in the region have few issues with. The advantage of having transitioned to democracy fairly recently is that this resulted in the almost universal adoption of a fair and modern electoral system.

Older democracies in the West are plagued by their legacy voting systems, making the switch to PR all the more difficult in the eyes of both the ruling parties and the general public.

We can only hope that emerging Europe will continue to be an example in the future, with Moldova reverting to PR, and the possibility of Hungary also ditching its parallel system if the anti-Viktor Orban coalition (the opposition will run joint candidates for the country’s FPTP seats) secures victory in 2022.

Unlike many news and information platforms, Emerging Europe is free to read, and always will be. There is no paywall here. We are independent, not affiliated with nor representing any political party or business organisation. We want the very best for emerging Europe, nothing more, nothing less. Your support will help us continue to spread the word about this amazing region.

You can contribute here. Thank you.

[…] Source link : https://emerging-europe.com/news/the-gallagher-index-who-has-the-regions-most-represen… Author : Publish date : 2021-04-02 23:00:09 Copyright for syndicated content belongs to the linked Source. Tags: CEE039semergingEuropeMontenegroparliamentrepresentative Previous Post […]

[…] Source link […]

[…] CEE on the Gallagher Index: Which country has the region’s most proportional parliament? […]

[…] Which country has the region’s most proportional parliament? […]

[…] CEE on the Gallagher Index: Which country has the region’s most proportional parliament? […]