From Ukraine’s bravery and resilience in the face of Russia’s brutal aggression to tension on the Kosovo border and in Nagorno-Karabakh, this is our review of 2022 in Central and Eastern Europe.

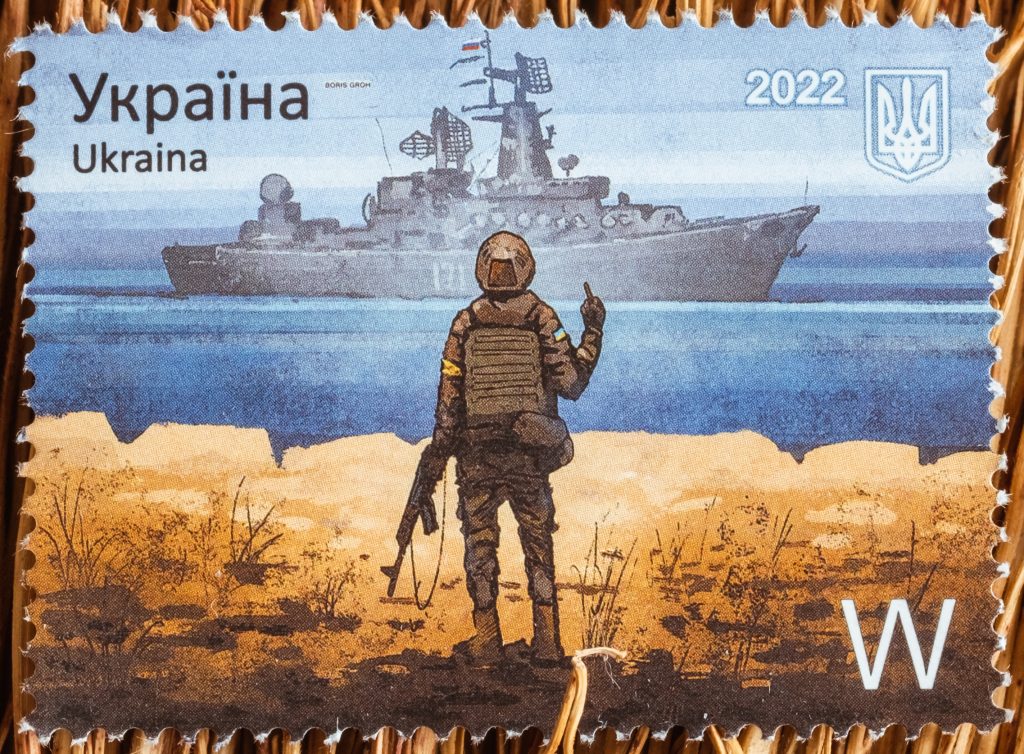

Russia launched a full-scale invasion of Ukraine on February 24 with the aim of toppling the government of President Volodymyr Zelensky in a blitzkrieg “special military operation” that it expected would last just three days.

More than 300 days later, Moscow has achieved none of its pre-war aims. Instead, almost 100,000 Russian soldiers have been killed, hundreds of thousands of young Russians have fled abroad for fear of being sent to fight, and the Russian economy, hit by severe sanctions, has tanked.

Russia has become arguably more isolated than at any time in the past century, Ukraine and neighbouring Moldova have been made candidates for European Union membership and two erstwhile neutral European states, Sweden and Finland, have been convinced of the need to join NATO.

“The Baltic Sea is now a NATO sea,” says former UK Foreign Secretary Malcom Rifkind, who in June received this year’s Günter Verheugen Award from Emerging Europe – one of many worthy winners this year. “It’s one of the direct consequences of the ‘strategic genius’ of Vladimir Putin.”

Ukraine, meanwhile, resists.

Early losses of territory in the west of the country, around the capital Kyiv, were reversed by spring. As Russia retreated, the horrors of life under occupation were revealed, despite Moscow’s attempts to cover its tracks and spread false news.

Part of Ukraine’s south and east remain under Russian occupation, including Crimea, and parts of four provinces “annexed” by Russia following a series of sham referenda in October: Donetsk, Kherson, Luhansk, Zaporizhzhia.

Ukraine’s economy has been remarkably resilient, despite the departure of around eight million refugees. Several million more have been displaced within Ukraine. Domestic consumption has been strong, and exports of IT products and services have held steady. Calling Russia’s bluff in order to keep alive a deal that allows the seaborne export of grain has helped Ukrainian farmers and lessened the threat of a global food crisis. Nevertheless, Ukraine’s GDP is expected to contract by between 32 per cent and 37 per cent this year.

The country is receiving around three billion US dollars per month in grants and loans from key allies (mainly the US and European Union), and the EU has just allocated a further 18 million euros for next year.

The total cost of reconstruction is not yet clear, since the war is ongoing and Russian troops are engaging in massive destruction. The Ukrainian government puts the bill for reconstruction at 750 billion US dollars over ten years (including military spending). Some analysts have suggested that Ukraine’s reconstruction plans need more work.

Struggling on the battlefield, Russia has in recent weeks been striking key Ukrainian infrastructure, which has led to towns and cities across the country going without electricity and heating for long periods. On December 29, a massive, coordinated missile attack left almost all of the western Ukrainian city of Lviv without electricity for much of the day. The aim is to demoralise the Ukrainian population. It will not work.

“[Russia] wants panic and chaos, it wants to destroy our energy system,” Zelensky said earlier this month. “But while there may be temporary power outages now, there will never be an interruption in our confidence – our confidence in victory.”

Little change in Hungary, stalemate in Bulgaria

Amidst yet another row with the European Union Viktor Orbán was formally sworn in as Hungary’s prime minister on May 16, the fifth time that the 58-year-old has taken the prime ministerial oath of office.

Orbán’s Fidesz party comfortably won a parliamentary election in April, despite Hungary’s major opposition parties uniting in attempt to defeat him. The playing field, however, was not level, claimed rights groups. Hungary’s run in with the EU continues, although earlier this month, spooked by the real possibility of losing out on billions of euros of EU funds, Orbán backed down and approved a crucial new aid package for Ukraine.

New battles with the EU await, however. Rule of law remains a huge problem in Hungary, but the same is true across much of emerging Europe and Central Asia. According to the World Justice Project, improvement in rule of law in Bulgaria, Estonia, Kazakhstan, Kosovo, Latvia, Lithuania, Moldova and Uzbekistan is being offset by stagnation or regression elsewhere.

Bulgaria held another parliamentary election this year (the fourth in just iver 18 months), which yet again ended in stalemate. There is a now a real risk that the country could soon return to the deadlock of 2021, a year in which Bulgaria held no fewer than three parliamentary elections.

That political crisis only came to an end when Kiril Petkov was sworn in as prime minister at the end of 2021 as part of a three-party coalition that promised to make fighting corruption a priority. The coalition lasted until June when a junior coalition partner, the populist There is Such a People party, quit over disagreements on spending and whether Bulgaria should back North Macedonia’s European Union accession.

Expect yet another election early next year.

No entry

Bulgaria did finally lift its veto to allow North Macedonia (and with it Albania) to commence EU accession talks in July, although neither country should expect actual membership anytime soon.

The same goes for all six countries of the Western Balkans, despite Bosnia and Herzegovina this month becoming a formal EU candidate, and Kosovo filing an application for EU membership.

For beyond the encouraging words and signals that emanate from Brussels from time to time, the region looks as far away from EU membership (something for which some countries in the region, such as Montenegro, have been waiting almost 20 years) than ever.

This month’s EU-Western Balkans summit in Tirana, Albania – the first to be held in the region – was light on content and empty on any kind of agreement on a way forward. The Tirana Declaration issued at the summit’s close “reconfirmed” the EU’s “full and unequivocal commitment to the European Union membership perspective of the Western Balkans” and called for the “acceleration” of the accession process.

Without EU-wide consensus however, there is little likelihood of any kind of acceleration taking place. Vienna’s veto last week of Bulgaria’s and Romania’s bids to become members of the Schengen, border-free travel zone is evidence that in some EU capitals any form of enlargement – even of the Schengen zone for countries which are already EU members – is off the table.

This is a shame, for Bulgaria’s and Romania’s failure to become members of the Schengen border-free travel zone will embolden anti-EU populists in both countries.

The ostensible motives behind Vienna’s stance look dubious. “It is wrong that a system that does not work properly in many places would get expanded at this point,” said Austrian Interior Minister Gerhard Karner.

And yet Austria was happy to give Croatia, which only became an EU member in 2013, six years after Bulgaria and Romania, the green light to join the Schengen area from January 1, 2023. Croatia will also become a member of the eurozone on January 1 (preparations for the big day have been under way for six months).

The Polish enigma

Poland remained emerging Europe’s biggest puzzle in 2022, staunchly supporting Ukraine and yet continuing to bait the EU at every opportunity.

Poland has welcomed, and continues to host, hundreds of thousands of displaced people from Ukraine. It has supplied Ukraine with arms and munitions, while the east of Poland has become a vital logistics hub for the transport of aid.

At various international organisations, including, ironically, the EU, Warsaw has offered Kyiv resolute diplomatic support. In May, Poland’s president, Andrzej Duda, was the first foreign leader to address Ukraine’s parliament since the start of Russia’s war.

As a result, Poland’s international reputation – in recent years dominated by criticism of its justice system, abortion rights, ‘LGBT-free’ zones, coal addiction and media freedom – has very quickly been, if not fully restored, then certainly well-polished. Accusations of “Ukrainewashing” are misplaced, however. There may be benefits for countries and politicians backing Kyiv, but these are not the primary motives behind their support.

Warsaw this year also began to (finally) seriously explore nuclear energy options, and yet it continues to come under criticism for the slow pace of its coal exit. Its urban-rural divide and inherent inequality continues to pose problems for policy makers. An enigma indeed.

An election next year, set to be held amongst a backdrop of high inflation and lower than expected economic growth, could be the most competitive for more than a decade.

Tensions high in Kosovo, Nagorno-Karabakh

Ukraine may be the only country in the emerging Europe region which was unfortunate enough to see full-scale armed conflict in 2022, but a few others came dangerously close – and remain so.

In Kosovo (a country we described in October as “an eternal asterisk”) tensions remain high amid a dispute with neighbouring Serbia over the implementation of new rules that will oblige the country’s ethnic Serbs to exchange their Serbian-issued car number plates and ID cards for Kosovan-issued ones.

The dispute has been at boiling point since the summer, when despite relations between the two countries plunging to their lowest ebb for some time, war appeared a remote prospect. It remains unlikely – the presence of NATO troops in Kosovo should guarantee that – but is no longer such a remote possibility. An informal deal, brokered by the EU and US, defused the latest flare up this week, avoiding armed conflict for now.

However, in the disputed region of Nagorno-Karabakh, the year ends with the all-too-real prospect of a new war breaking out between Armenia and Azerbaijan.

The Lachin Corridor, the sole road connecting Nagorno-Karabakh with Armenia, has been blocked by Azeris claiming to be environmental activists since December 12, disrupting access to essential goods and services for tens of thousands of ethnic Armenians living there.

The ‘activists’ are demanding access to mining sites in areas under the control of the de facto authorities in Nagorno-Karabakh, claiming that they are illegally exploiting gold and copper molybdenum deposits and using the Lachin road to transport those minerals to Armenia.

Russian peacekeeping forces, who have been guarding the road since a 2020 war between Armenia and Azerbaijan over Nagorno-Karabakh ended, have come under fierce criticism from Armenia’s prime minister, Nikol Pashinyan, for allowing the situation to escalate.

Unlike many news and information platforms, Emerging Europe is free to read, and always will be. There is no paywall here. We are independent, not affiliated with nor representing any political party or business organisation. We want the very best for emerging Europe, nothing more, nothing less. Your support will help us continue to spread the word about this amazing region.

You can contribute here. Thank you.