You may not want to look back too carefully at a year many of us will no doubt wish to forget, but we have put together a recap of 2020 in the emerging Europe region nevertheless. It was grim at times, Covid-19, war and attacks on democracy seemingly ever-present. But it wasn’t all bad.

We started the year with a story of love, set mainly in old Baku, Azerbaijan.

It’s the story of Ali and Nino, a sweeping novel of romance and adventure which tells the tale of Ali, a Muslim schoolboy from an aristocratic Azeri family who falls in love with Nino, a beautiful Christian girl with distinct European sensibilities. In order to be together they must overcome personal scandal, family blood feuds, World War I and the Bolshevik revolution.

Their tale is the subject of emerging Europe’s most moving – in every sense of the word – statue, in Batumi, Georgia, a city we had recently visited, the last of many trips during 2019.

Covid-19

Who knew that we would make just one more trip before emerging Europe began to shut down, as the Covid-19 pandemic advanced across the continent.

That trip was to Estonia, where we saw for ourselves the wonder that is that country’s digital society.

That article prompted a response from one disgruntled reader (presumably not from Estonia) claiming that we write far too many nice things about the place. Later in the year I explained why, and offered a few ideas as to how other countries can also get some get good press, here.

In fact, at the beginning of the pandemic at least, most of emerging Europe (not least Georgia) was getting some great press, as the spread of the virus was far less pronounced in the region than elsewhere in Europe, mainly as a result of strict lockdowns being put in place quickly.

In reality, the region was merely delaying the spread of the virus.

Right from the start, warnings of economic hardship were never far away: the Vienna Institute of International Economic Studies (wiiw) was one of the first think tanks to claim that the economic impact of coronavirus on emerging Europe would be the worst since the global financial crisis of 2008.

It was, alas, correct, and until the Covid-19 vaccine – which Hungary became the first country in the region to begin to rollout, on December 26 – becomes ubiquitous, the slump may go on.

Countries outside the EU, which do not have access to as many doses of the vaccine as EU member states, may face longer economic declines. Eastern Europe and Central Asia in particular face huge problems as remittances slow to a trickle.

The EU needs to step up to ensure that the vaccine-led recovery benefits all countries in the emerging Europe region. If it doesn’t, then other, less benevolent would be donors will.

Ever since the beginning of the coronavirus crisis, there has been a great deal of talk about how it would accelerate digitalisation across the region, that all countries would become more like Estonia.

This has largely been the case, but as I warned in March, simply moving offline bureaucracy online is not real digitalisation, nor can online teaching genuinely be termed digital education.

Nevertheless, thinking digital remains crucial to ensuring a speedy recovery, not least for trade.

Belarus

One of the first casualties of Covid-19 was sport, which shut down across the world. Everywhere except Belarus, that is, where football continued (to the delight of gamblers and online betting companies across the globe).

It was an early example of the utter disdain that the country’s president, Alexander Lukashenko, has for the health of Belarusians. He infamously claimed that drinking vodka and driving tractors would repel the virus.

In August, Lukashenko was defeated in a presidential election by Svetlana Tikhanovskaya, the wife of a jailed YouTube vlogger. The dictator claimed victory regardless (with 80 per cent of the vote, no less), prompting mass protests that continue to this day.

Tikhanovskaya was soon forced into exile, in Lithuania, from where she continues to coordinate the country’s opposition movement.

Thousands of others have been arrested, jailed, and many tortured. Protest has become a way of life, but Lukashenko clings on. Eventually, it could be the state of the country’s increasingly precarious economy that does for him.

Elections, and war

There were other presidential elections of note in the emerging Europe in 2020, not least in Poland, where, despite a brave challenge from Mayor of Warsaw Rafał Trzaskowski, conservative incumbent Andrzej Duda won a second term in office. The country is nevertheless more divided than ever, and remains at loggerheads with the European Union over all sorts of issues, from LGBT+ rights to the rule of law.

So much so that together with the EU’s other black sheep, Hungary, it came close to vetoing the EU’s next budget and Covid-19 recovery package, dubbed Next Generation EU. Some analysts suggested the pair – who need the EU’s money as much as any other country in the bloc – were bluffing. A last minute compromise means that we are unlikely to ever find out.

There was good news from Moldova (not a phrase used all that often) where Maia Sandu defeated Igor Dodon to become the country’s first female president and will hopefully offer Europe’s poorest state a fresh start. Shortly afterwards we were forced to point out however that framing Sandu’s victory in strictly ‘pro-European candidate defeats pro-Russian’ terms was wrong. It really is time – and not just in Moldova, it has been a ‘feature’ of reporting from Belarus too – to ditch the ‘pro-European’ and ‘pro-Russian’ epithets.

Armenian Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan, who has at times been bracketed as both ‘pro-European’ and ‘pro-Russian’ and who was one of a few emerging Europe leaders to survive a bout of Covid-19 (Ukraine’s Volodymyr Zelensky was another) may not survive the fallout from Armenia’s military defeat in a brief but bloody war with Azerbaijan over the disputed region of Nagorno-Karabakh.

Amnesty International has claimed that both sides committed war crimes.

Armenia, Azerbaijan and Russia signed an agreement to end the fighting on November 10, just hours after Armenian officials confirmed that the key city of Shusha (known as Shushi in Armenia), the second-biggest city in the enclave, had been taken by Azeri forces. Mr Pashinyan has described the peace deal as “unspeakably painful”, sparking a violent response in Armenia, with angry protesters storming government buildings in Yerevan where they ransacked offices and broke windows.

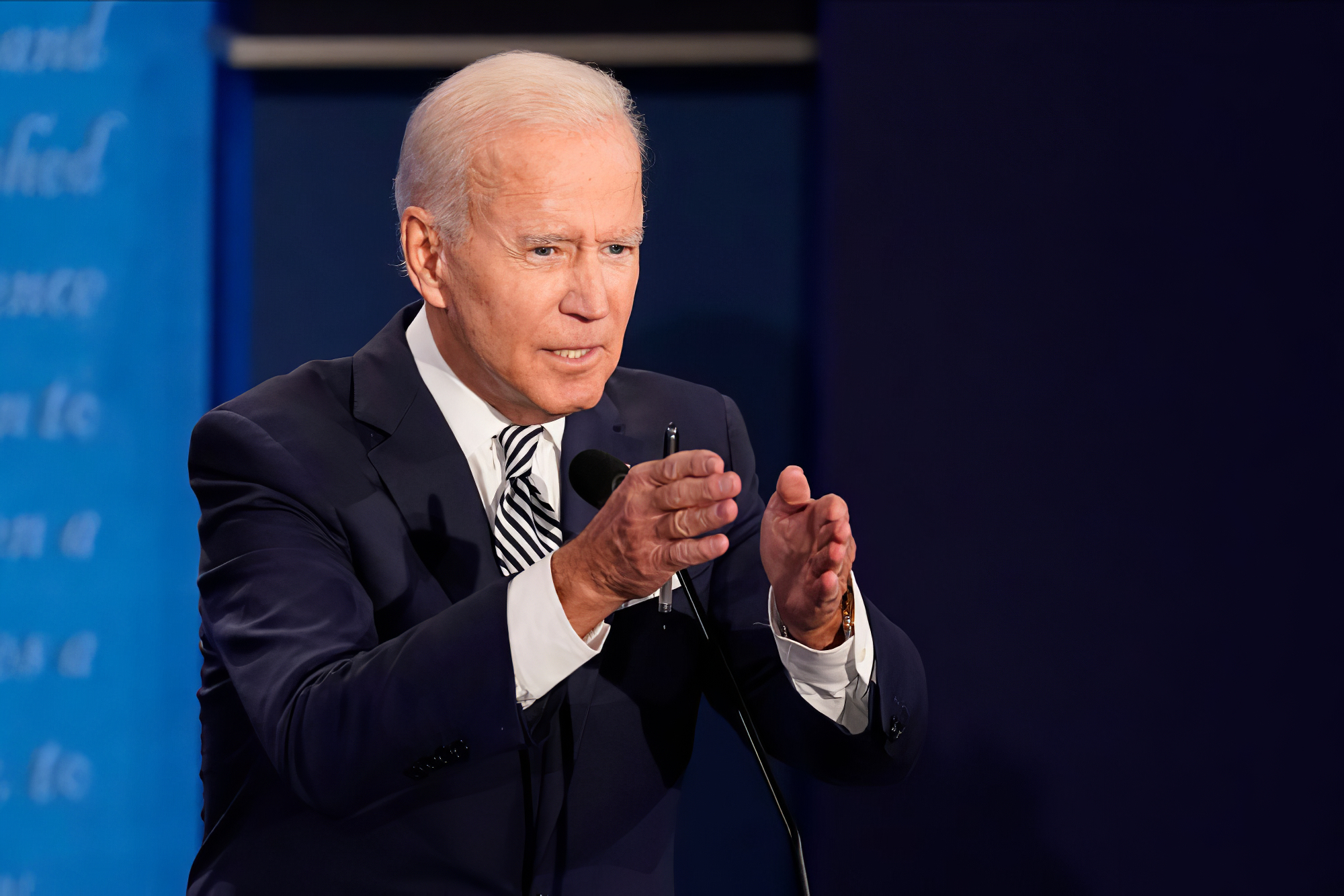

A change at the White House

Next year will see a change in personnel at the White House in Washington, with Joe Biden replacing Donald Trump as US president. The world can look forward to four years of measured, hands-on diplomacy, getting the US back on the climate change train and seeking to reinforce the Iran deal. What is less certain is the Biden administration’s policy towards Eastern Europe.

A Biden administration is more likely to return to traditional European NATO allies such as Germany and France and will certainly fawn less over Poland and Hungary, which was Trump’s playground over the past four years.

It also remains to be seen how the Biden administration will respond to the restart of construction on Russia’s controversial Nord Stream 2 gas pipeline, which the US has long opposed.

At year’s end, construction of the pipeline edged closer to completion following the laying of a 2.6 kilometre section of pipes in German territorial waters, despite the threat of US sanctions.

The consortium behind the project will now proceed to lay the last remaining pipes, in Danish waters. It has not said when this will happen, but we can expect a major row when it does.

As if Covid-19, war and geopolitical disputes were not enough, 2020 had a final sting in its tail in the shape of a major earthquake that hit Croatia on December 29, killing at least seven people.

“My town has been completely destroyed. We have dead children,” Darinko Dumbović, the mayor of Petrinja, the worst hit town, said in a statement broadcast by Croatian TV station HRT. “This is like Hiroshima – half of the city no longer exists.”

The year in culture

Like much else in 2020, culture moved online, and both artists and venues had to adapt to the new realities of social distancing.

There was renewed interest in films from the emerging Europe region, as people looked for something a little different to watch. We selected five Polish classics now available on Netflix: it turned out to be one of our most popular articles of the year.

Later in the year the Latvia’s National Film Centre offered a treat for all cinephiles interested in international movie history, making a wide collection of classic and significant Latvian movies available to stream online free of charge, complete with subtitles in English and several other languages.

From Romania there was Collective, named by former US president Barack Obama no less as one of his films of the year. A brilliant documentary about a tragic nightclub fire and its aftermath, as well as corruption in the Romanian healthcare system, it increasingly looks like a shoo-in for Best International Feature at next year’s Academy Awards.

Meanwhile, with media freedom increasingly under pressure in the region, the third and final season of Croatian TV drama The Paper (Novine), which debuted on Croatian HRT this year, was as timely as it gets. Less welcome was another Borat film, although Kazakhstan’s response to it did at least suggest the country has grown up, even if Sacha Baron Cohen hasn’t. (By the way, here are five films about Kazakhstan actually worth your time).

When sport resumed in the autumn, Slovenia dominated the Tour de France, with Tadej Pogačar and Primož Roglič taking the first two spots in the general classification. Roglič would also win the Vuelta a España and the Liege-Bastogne-Liege classic, and was named cyclist of the year by Vélo Magazine, the world’s leading cycling publication.

Music provided much solace during 2020, with Belarusian post-punk possibly the year’s perfect soundtrack. An artist from Poland meanwhile, Wojciech Szczepanik, created the world’s first carbon neutral album.

For classical musicians, the absence of an audience was a genuine loss, as Georgia’s UNESCO artist for peace Elisso Bolkvadze told us in an interview, in which she also discussed her new role as a politician.

For those of us who claim to have “spotted her early”, 2020 was the year Kosovo’s finest and probably emerging Europe’s biggest ever pop star Dua Lipa gave us the opportunity to say “we told you so”. She was the pop star the year needed, her Studio 2054 extravaganza – streamed to the world at the end of November – crashed into our living rooms like a well-oiled party guest who has suddenly decided it’s time to start spraying everyone with champagne.

It was an interlude of hedonistic joy in a year otherwise short of such moments.

A different Emerging Europe

One of the many casualties of Covid-19 restrictions was the Emerging Europe Awards ceremony, originally set to be held at the European Parliament in June. The show went on, however, with the laureates being named online.

The first was Emerging Europe’s Public Figure of the Year, an award which went to European Public Prosecutor Laura Codruţa Kövesi, rose to prominence in her native Romania as the boss of the country’s National Anti-Corruption Directorate, the DNA, of which she became director in 2013.

The Hungarian capital Budapest was named emerging Europe’s most business-friendly city, and Enterprise Estonia the region’s leading investment promotion agency.

Former Swedish Prime Minister Carl Bildt and Bosnian musician Goran Bregović were named as the recipients of Emerging Europe’s Remarkable Achievement Awards for 2020, with Mr Bildt handed the Professor Günter Verheugen Award, which recognises the work of those born outside of the emerging Europe region for their work within it, with Mr Bregović, one of emerging Europe’s best-known modern musicians and composers, taking the Princess Marina Sturdza Award, which rewards those born within the region for their work promoting it worldwide.

Olga Tokarczuk’s Nobel Prize Lecture meanwhile was named Emerging Europe’s Artistic Achievement of 2020. The Polish writer won the 2018 Nobel Prize for Literature for her “narrative imagination that with encyclopedic passion represents the crossing of boundaries as a form of life”.

As the year came to a close, for Emerging Europe there were new beginnings, in the form of Tech Emerging Europe Advocates (TEEA), successfully launched on November 24. TEEA is now officially a part of Global Tech Advocates (GTA), the world’s only global tech community, whose members include tech leaders from Silicon Valley to Europe, Asia and Australia/New Zealand. We look forward to developing the network next year, when – hopefully – we will again be able to network in person.

Finally, as we move into 2021, its worth thinking about what comes next.

In June, I wrote that “plugging the world back in” should not be an option. I stand by that (even if my suggestion that “the worst has passed” now looks horribly inaccurate).

But my closing statement remains valid:

“Many years ago a university professor of mine, well ahead of the curve when it came to recognising the threat posed by climate change, lamented the fact that people would never vote for the kind of change we need to bring about in order to genuinely make the world a greener, more fair and better place. It is my belief – Panglossian as it may be – that the reaction to Covid-19 has proven him wrong. What we need to do now is to nurture and support those movements – especially from the civil society sector – which are committed to bringing about the change that we need. We have been given a chance to finally get it right, to finally reset the planet. We may not get another.”

Let’s drink to that, to a better 2021, and to a better world.

Happy New Year.

—

Unlike many news and information platforms, Emerging Europe is free to read, and always will be. There is no paywall here. We are independent, not affiliated with nor representing any political party or business organisation. We want the very best for emerging Europe, nothing more, nothing less. Your support will help us continue to spread the word about this amazing region.

You can contribute here. Thank you.

Add Comment